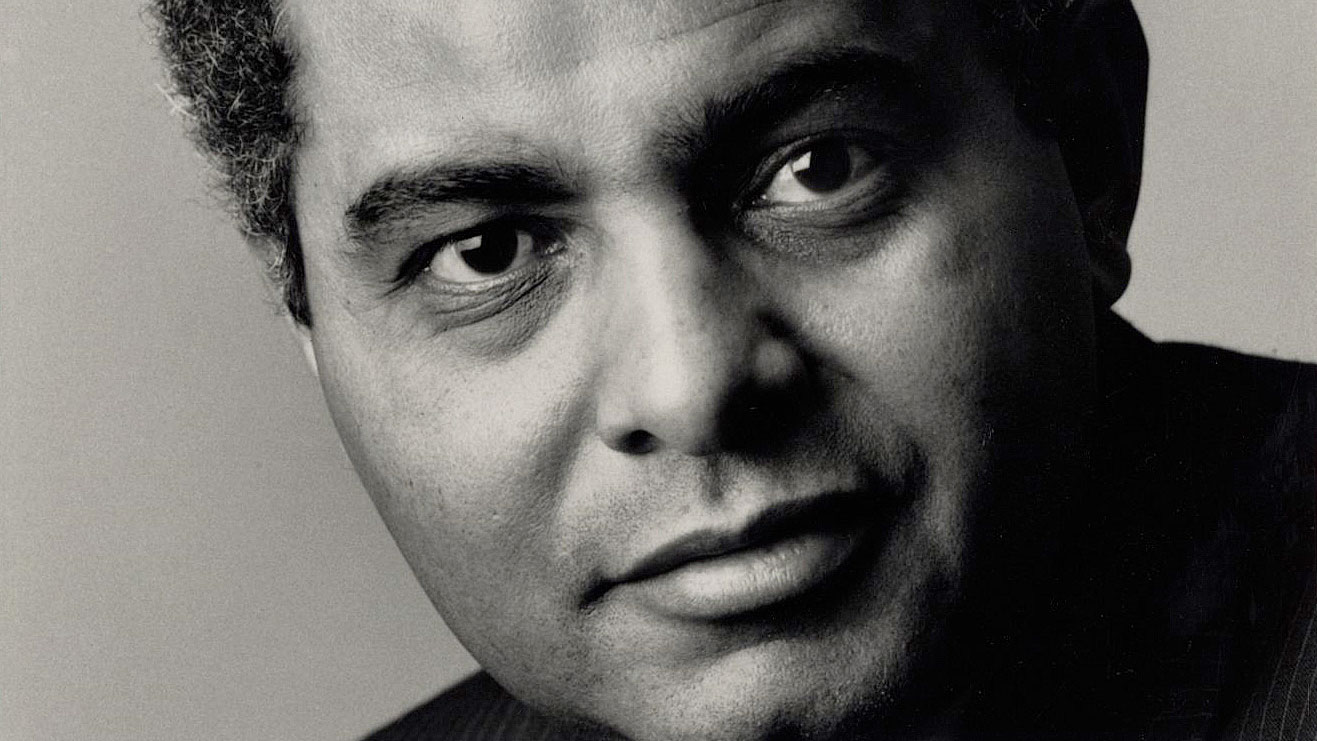

Steven A. Minter, a great luminary in the global field of community philanthropy, has passed away. Minter, the 8th president and CEO of the Cleveland Foundation and the first African American president of any U.S. community foundation, leaves behind a legacy of inspired leadership, philanthropic innovations and advances for all people of Greater Cleveland. The Cleveland Foundation board, staff and donors send our deepest condolences to his family as we mourn the loss of a titan in our field and a tremendously compassionate, genuine and humble leader and friend.

An Akron native, Minter served as CEO from 1984 to 2003 and deepened the foundation’s involvement with what he came to call the “enduring issues” of public education, jobs, housing and health care. During his tenure, $1 billion was added to the foundation’s endowment from among bequests, promotion of supporting organizations and organizational funds, the launch of donor-advised funds, and market performance.

Consequently, grantmaking income of the people’s foundation increased by 450% under his leadership, only strengthening the foundation as a potent agent working to effect progressive socioeconomic change in our community. At the time of his retirement, he was widely regarded as the most successful among the 700 chief executive officers of U.S. community foundations and was honored with the Council on Foundations Distinguished Grantmaker Award for lifetime achievement in philanthropy.

Read the full eulogy that Ronn Richard delivered at Steve Minter’s November 2 memorial service here.

A Remembrance of Steve by Cleveland Foundation President & CEO Ronn Richard

Steve Minter and Ronn Richard talk together before the start of the Cleveland Foundation Centennial Meeting in 2014.

There are people you meet in your lifetime who you immediately know were put on this earth to be a powerful, life-changing force for good – Steve Minter was one of those people

Steve started his career as a social worker, and became one of the most respected leaders in Greater Cleveland and in the field of American philanthropy. Optimistic, brilliant, diplomatic and kind, Steve led by bringing out the very best qualities of those around him.

For nearly 30 years at the Cleveland Foundation, including two decades as the first African American CEO of a community foundation, Steve deepened our involvement with what he came to call the enduring issues of public education, jobs, housing and health care—the issues that define our work to this very day. His first purpose was to serve the citizens of Cleveland, and the hundreds of people he mentored, many of whom dedicated their lives to public service because of the path he forged for all of us.

He was an inspired teacher, and most important, an incredible friend to whom we are deeply saddened to say goodbye. It is exceedingly difficult to lose this man, among the very best we’ll meet, but it is heartening to know that he now joins his beloved Dolly. I am certain his example will continue to lift the people and city he loved for decades to come.

Steve Minter’s Impact on Greater Cleveland and Beyond

Reflections and records of Steven minter’s work at the foundation

In recognition of Minter’s retirement in 2003, the foundation produced “A Foundation for Growth: The Dramatic Work of Steven A. Minter and the Cleveland Foundation,” a collection of stories, reflections from the community, and anecdotes from Minter and his staff. It can be viewed in full below, along with excerpts from the foundation’s centennial history website chronicling three of the foundation’s transformational efforts under Minter’s leadership.

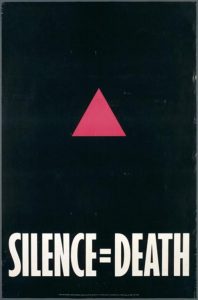

1986 | JOINING THE EARLY BATTLE AGAINST AIDS

The foundation’s support for preventative education and proactive treatment helped to lessen the disease’s impact in Cuyahoga County.

The Cleveland Foundation’s consistent support of efforts to battle AIDS began only a year after U.S. health officials coined the disease’s name: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. In 1983, foundation staff met with the City of Cleveland’s health commissioner and encouraged the city to move forward with planning for a widespread education program targeted at high-risk groups. In 1986, the foundation followed up with a $67,000 grant for the city’s first public awareness campaign. Spearheaded by program officer for health Robert E. Eckardt, these initiatives stood in marked contrast to the attitude adopted in other peer Midwestern cities, where AIDS was still misunderstood as affecting only the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) community, rather than as a major public health threat.

Although spared the brunt of the epidemic, Cleveland saw a doubling of reported AIDS cases every year between the early 1980s and 1988, when Eckardt joined forces with his counterpart at Cleveland’s George Gund Foundation to push for the city’s inclusion in a demonstration project initiated by the Ford Foundation to stimulate a community-wide attack on the disease in nine metropolitan areas. Ford’s National Community AIDS Partnership Project was based on Cleveland’s response to the epidemic. The Cleveland and Gund Foundations raised $1 million for project grants that helped to pave the way for what became a collaborative, broad-based response to AIDS in Greater Cleveland.

With continuing financial support from the two foundations, a Citizens Committee on AIDS/HIV was convened in 1992. The 13-member committee (which included a number of persons living with AIDS/HIV) reviewed service and funding gaps and developed an action plan out of which grew the AIDS Funding Collaborative (AFC). Supported by Cleveland and Gund, the Cuyahoga County Commissioners, United Way Services and the National AIDS Fund, AFC awarded grants to implement the citizen committee’s wide-ranging recommendations and encourage the community’s coordination of services. Since its inception in 1994, AFC has distributed more than $8 million to private and public-sector providers for research, treatment and related social services.

In the period before early screening tests and improved antiretroviral treatments transformed AIDS into a long-term chronic disease for most patients in the United States, the Cleveland Foundation’s advocacy of preventative education and proactive healthcare programs helped to lessen the disease’s impact in Cuyahoga County.

1986 | TURNAROUND IN HOUGH

Privately developed Beacon Place Townhomes on East 82nd Street—evidence of the return of middle-class Clevelanders to the central city.

The foundation’s championship of a unique proposal to build townhomes near the flashpoint of the Hough riots marked the beginning of reinvestment in the central-city neighborhood.

In the early 1980s the Cleveland Foundation helped finance Lexington Village, the first market-rate rental housing built in the east-side Cleveland neighborhood of Hough in 50 years, precisely because it was a “project of scale,” not a small program that tinkered at the edge of a problem. The 183 townhomes proposed for Phase 1 of Lexington Village had the potential to offer a turnaround solution for disinvestment in the predominately African-American neighborhood, which had never been rebuilt since being engulfed in riots in 1966.

The opportunity to stem the neighborhood’s continuing decline was presented by the Famicos Foundation, a nonprofit developer of housing for low-income families, whose director approached the Cleveland Foundation with a unique proposal to build rental property at Lexington Avenue and East 79th Street, near the flashpoint of the Hough riots. The foundation’s program officer for civic affairs (and future director), Steven A. Minter, embraced the quixotic project. He recognized the immediate benefits for a neighborhood of which he had become a dedicated champion during his days as a caseworker for the City of Cleveland’s welfare department. Minter also saw the project’s potential to provide concrete evidence that middle-class suburb dwellers, provided the proper inducements, could be persuaded to live in and help to revitalize central-city neighborhoods.

The civic affairs program officer persuaded the board to make a program-related investment of $800,000 in Lexington Village—only the second time to date that the foundation had used the still-unconventional tactic of investing principal in a project. Minter then went on to assemble a coalition of 27 public and private lenders that provided the additional $13.3 million in needed working capital.

The marketing of the Phase 1 units, completed in 1986, was so successful that another $6.4 million in bank loans and private-sector and foundation investments was raised to build 93 more units on adjacent land. As the foundation had believed, Lexington Village set off a chain reaction of new development in Hough, including the Church Square shopping center, additional townhome complexes along the main arteries of Chester and Euclid Avenue, and the construction of single-family residences on side streets. Hough is no longer a dead zone, and redevelopment is slow but ongoing.

1996 | REFORMING PUBLIC SCHOOL GOVERNANCE

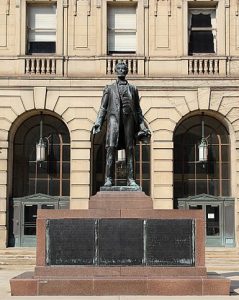

The Board of Education building in downtown Cleveland, longtime headquarters of the system’s central administration

The directors of the Cleveland and George Gund Foundations chaired a nonpartisan study commission that led to voter approval of mayoral control.

Steven A. Minter felt duty-bound to accept Cleveland mayor Michael R. White’s request that he co-chair the Mayoral Commission on School Governance in 1996. The Cleveland Foundation had a long tradition of leading efforts to improve the public schools, and the foundation’s seventh chief executive was personally devoted to education reform.

During the first three years of Minter’s tenure, the foundation had stepped forward to make the lead commitment to a $16 million philanthropic-corporate partnership called the Cleveland Initiative for Education (CIE), which sought to establish universal postsecondary scholarship and employment programs requested by the system’s superintendent as incentives for his students. Minter deemed the initiative so critical to the well-being of the city and its children that he joined the CIE board and helped guide its evolution into a broad-based coalition working to effect school improvement on multiple fronts.

Minter’s new assignment came as a result of a proposal floated by two Ohio General Assembly members recommending that control of the state’s failing public school systems be vested in the top elected official of the system’s home city. If adopted (as similar legislation had been in Chicago), Clevelanders would no longer elect school board members.

The prospect of losing hard-won voting rights did not sit well with many of Cleveland’s African-American leaders, and the leaders of the Cleveland Teachers Union were opposed to ceding control of the schools to a politician with whom they had publicly wrangled over contract negotiations. Yet “mayoral control” seemed to be making a difference in the performance of the Chicago schools. A nonpartisan study of the concept, Mayor White recognized, might help to ensure it a fair hearing in the General Assembly. To chair the study, he looked to civic leaders who could be counted on to do a thorough examination and who would be perceived as having no axes to grind: Steve Minter and David Bergholz, then executive director of the George Gund Foundation.

Like all champions of public education, Minter had watched with increasing concern the comings and goings of 14 Cleveland schools superintendents and the dysfunction of the system’s elected board. The board proved incapable of heading off either state control, which the federal courts imposed on the system in 1995, or the “fiscal emergency” declared by the state auditor in 1996. Finding these developments intolerable, Minter had given considerable thought to the issue of school governance and believed that mayoral control might be a workable alternative.

To inform its deliberations, the Mayoral Commission on School Governance conducted research, sought perspective from national experts and held public hearings that brought out contentious opposition to the concept of an appointed school board. Minter knew the hearings would change no minds, but believed them necessary to the integrity of the study process. He did not want it said that the commission had ignored legitimate concerns. Minter took special pains to solicit the feedback of then U.S. Congressman Louis Stokes, who had represented Cleveland’s 11th District since 1970 and whose opinions counted with both the public and the powers-that-be. The congressman helped to shape a positive outcome by vetoing the idea of having suburban representatives on the appointed board and making his opposition to mayoral control known without mounting the barricades.

The commission issued its final report in December 1996, arguing that “those involved in governance must have the ability to make a variety of financial, policy and other strategic decisions that will effectively chart the correct course of the Cleveland Public Schools…. We believe these types of skills can best be brought to bear through an appointed board structure.” The commission co-chairs succeeded in moving “the debate beyond the political to considerations of management and education,” according to Mayor White.

The Ohio General Assembly ushered in a new day for the Cleveland public schools by enacting legislation that enabled the city’s mayor to name a chief executive officer of the public schools and appoint a nine-member board of education. The legislation called for a referendum on mayoral control after four years. When the vote came on November 5, 2002, more than 70 percent of the city’s electorate said yes to the perpetuation of the untraditional governance model that has been essential ever since to the initiation of substantive efforts to improve Cleveland’s public schools.

Steven Minter: The Work in His Own Words

These are highlights from a presentation former Cleveland Foundation President and CEO Steven A. Minter gave to the Cleveland Foundation staff on Sept. 10, 2013.

Staff photo of Steve Minter

Cleveland Foundation President and CEO, Steve Minter

Ronn Richard and Steve Minter alongside photographs of the Cleveland Foundation’s past presidents

Steve Minter joins Ronn Richard at the podium at the 2014 Centennial Meeting

Steve Minter and retired four-star general Colin Powell shake hands at the 2014 Centennial Meeting

The Minter family applauds with the audience at the Cleveland Foundation 2015 Annual Meeting

I am so saddened to hear of Mr. Minter’s passing. I am sending my condolences to his family and keeping them in prayer.

Joyce L. Walker