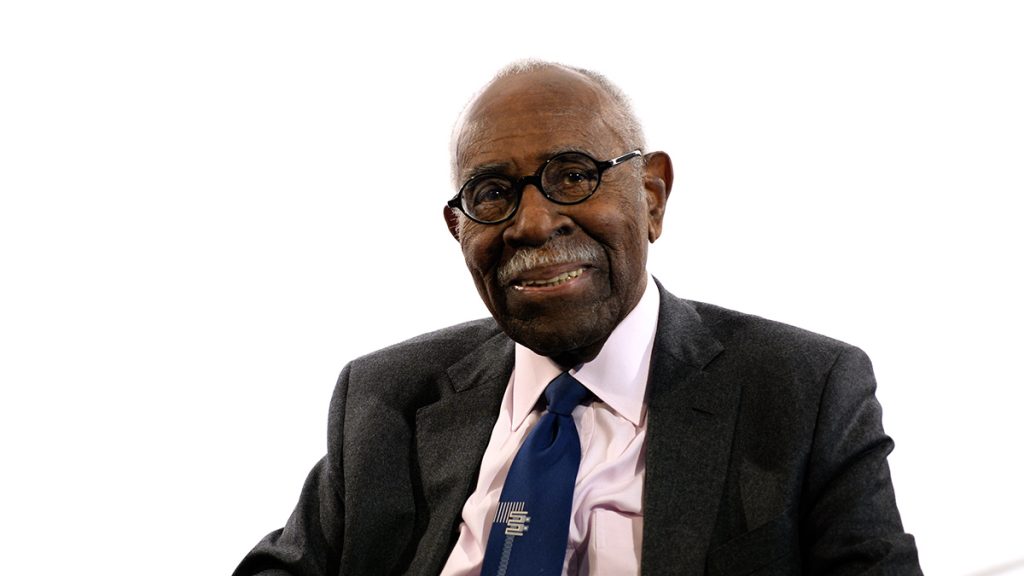

Robert P. Madison always dreamed of becoming an architect, but as an African American man growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, social inequality continuously tried to block his path to success. After overcoming countless obstacles, Madison achieved his goals by establishing a successful architecture firm that celebrates diversity, as well as a scholarship fund through the Cleveland Foundation that supports African American students pursuing a career in architecture. The story of his perseverance and generosity was celebrated at the 2018 African American Philanthropy Summit, where he shared how his education and professional background helped inform his philanthropic passions. Stay tuned for additional stories throughout Black Philanthropy Month “Celebrating the Faces of African American Philanthropy” in this six-part series. For more on Madison’s story, check out the Winter 2014 cover of “Gift of Giving” magazine.

What is your definition of philanthropy? Why is philanthropy an important theme in your life?

Bob Madison: I would define philanthropy as that desire to help humankind. I think all of us are endowed with certain assets, and I think it’s quite important, and desirable, to contribute those assets to make society a much better place in which we all live.

Why did you gravitate toward the architecture field?

Madison: When I was in first grade, I came home and was enjoying what I had made in school, and my mother said, ‘Son, you ought to be an architect.’ My father was an engineer, and back in those days, they didn’t hire colored people. He wanted to teach at a university, but he could not practice because nobody gave him an opportunity. My mother said, ‘One day we’re going to have an office of our own, and we will never have to ask anybody to hire us.’ She said, ‘Bob, you’re going to be an architect.’ That’s all I’ve ever done. That’s all I’ve ever dreamed of all my life.

What obstacles did you have to overcome to get to where you are today?

Madison: First of all, I started studying architecture after graduating East Tech. I went to Howard University, which is my father’s school. Then, the second world war came. After the war was over, I was wounded, but I had the G.I. Bill of Rights, which meant that anybody who had served in the military could go to university. I went to study at Western Reserve University, and the dean of the school of architecture said to me, ‘We don’t have colored people go to this school and I doubt we ever will.” I don’t like to take no for an answer. The next day, I came back up there and talked to the Dean of Admissions. I took examinations all that summer to be sure that I could qualify to go to their school. I was admitted. I guess that was a little difficult, but I didn’t get discouraged. I went to Reserve and graduated. There were a number of instances during school that they tried their best to discourage me, and even tried to flunk me out. They gave me all the hard courses. When I graduated, the Dean said to me, ‘What, Mr. Madison, are you going to do now? Go to work in a lumberyard?’ I told him, ‘No, no, Dean, I’m going be an architect.’ He was right, there weren’t any jobs for colored people because I went to several offices in the Cleveland area and they said, ‘No, you can’t fill out an application. We don’t hire colored people.’ I don’t like to take no for an answer, so I said, ‘I know my professor had a firm, and I’m going to go down to see him.’ Sure enough, I knocked on his door. I said, ‘I’ll work for you for free for two weeks, then, you can decide if you want to hire me or not.’ Two weeks later he called me back. He said, ‘Yeah, you come work for me.’ He had to ask every tenant on each floor if I could come to work at that office. This is 1948 now, and apparently, they said yes, so I worked there. I had to find a way, so I did.

How did your architecture scholarship begin? Why is that important to you?

Madison: A lot of people who worked for me were African Americans who wanted to be architects. Most of them got their basic training in my office. When we opened my office, I said, ‘We hire colored people, white people, black people, brown people, yellow and red people,’ and we did. I have a picture taken of the staff, it’s remarkable, and I am proud of that because this is what America really is all about. I also was aware that the students were not pursuing architecture like I hoped they would, and I said if it’s because of finances, then we ought to be able to do something about that. I had been in practice, July 17th, 2004, 50 years, so my wife and my brothers said let’s have some kind of a celebration. That year, we had a great party to celebrate the 50th year of my practice, and it was at that time that we started to endow a scholarship for students who wanted to study architecture. I feel very good that there is an opportunity for these youngsters to get a chance. I’m trying to keep on having money put into the endowment so it can grow larger.

You have earned the prestigious Frederick Harris Goff Philanthropic Service Award and been inducted into the Cleveland Foundation Centennial Society. Did you ever expect either of these honors?

Madison: No, I never did. First of all, the Cleveland Foundation, that’s a phenomenal institution to get anything from. The Cleveland Foundation is really a feather in your cap. The other thing was that I didn’t know you rewarded somebody for doing what they thought was the right thing to do. It was great and the reception I got and the letters I received, they made it all really wonderful.

What role do you believe philanthropists play in the future of Greater Cleveland?

Madison: I think it’s very important. I’m getting up in years now, and I’m looking back and realizing that there are a lot of people out there who are struggling. We have certain inalienable rights, but everyone doesn’t have the same opportunity. I really feel that if we are trying to establish a better world, and I think we are, it’s a recognition that all our citizens should have an opportunity to express themselves and to contribute. I had about 120 people in my office at one time. It was a joy to see those people working together of all colors, varying education levels, some from very poor circumstances and some from the aristocracy. I think that when our society gets a joy out of seeing all of our citizens participating in at least the most basic pleasures of a society, that’s who we should be, and I know philanthropy is important in making that happen. I look around and I see so much happening and so much need. I think the Cleveland Foundation is trying to make this a better world by assisting its people.

What would you say to individuals who want to be philanthropic but feel that they must be wealthy to give?

Madison: Do you have to be wealthy? I’m not wealthy, but I think that if each of us reviews our condition of life, health, endeavor and education, we can see there’s inequality. It’s important that we recognize that there is a joy that comes in sharing. As far as wealth is concerned, it’s more subjective. I’m wealthy because I’m 94 years old, and I’m happy and healthy. Wealth is not an issue, it’s only in your ability to understand that there is a surplus in whatever you do, and you won’t miss it. But what a joy comes about when you realize what you’ve done can help somebody. I can tell you that all the people who come to my office who I helped, I feel good about it. It is not wealth or money that’s really an issue here at all. Whatever we have, we can share it.

Why did you partner with the Cleveland Foundation?

Madison: That’s very simple: there’s only one. The Cleveland Foundation is the ‘le creme de la crème,’ as they say in French. The Cleveland Foundation is number one, and that’s what I’ve tried to be all my life.

The African American Philanthropy Committee was created in 1993 to promote awareness and education about the benefits of wealth and community preservation through philanthropy. The committee convenes a Philanthropy Summit once every two years to raise the visibility of African American philanthropy in the region and to honor local African American philanthropists. Save-the-date for the next Cleveland Foundation African American Philanthropy Summit, “2020 Vision: Disrupting the Cultural Landscape through Philanthropy,” in April 2020, and give online to the African American Philanthropy Committee Legacy Fund.

To learn more about becoming a donor and making your greatest charitable impact, visit www.ClevelandFoundation.org/Give.

The Cleveland Foundation is proud to have provided early funding that made it possible for two upcoming exhibits to travel to Cleveland. Check out:

- The Soul of Philanthropy: Reframed and Exhibited, a multimedia re-imagining of the book Giving Back by author Valaida Fullwood and photographer Charles W. Thomas. The exhibit, which conveys and celebrates traditions of giving time, talent and treasure in the African American community, will be on display from Sept. 6 – Dec. 6, 2019, at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

- seenUNseen, a collection of the works of some of the top African American artists dating back more than a century. On loan from the collection of longtime postal worker Kerry Davis, these objects are on public display for the first time outside of Atlanta. The show, which also includes more than 60 works from local and regional artists, will run from Sept. 20 – Nov. 16, 2019, at the Artists Archives of the Western Reserve and The Sculpture Center.